An in-depth technical guide for DBAs, SREs, and Data Architects.

PostgreSQL is, without exaggeration, one of the most impressive and complex pieces of software engineering of the last decades. Compliance with SQL standards, robustness, and extensibility have made it one of the most used databases in modern IT infrastructure, replacing giants in Fortune 500 companies and unicorn startups. However, this power comes accompanied by abysmal complexity and an even deeper need for tuning and performance adjustments. The postgresql.conf file is not a list of preferences, but a complex control panel that will directly impact your operation.

For Platform Engineering teams, DBAs, and SREs, adjusting parameters like work_mem, shared_buffers, effective_io_concurrency, or max_wal_size is a mystified ritual. The challenge lies in the dynamic nature of workloads: a configuration optimized for massive data ingestion (Write-Intensive) on Monday morning can be the catastrophic bottleneck for analytical reports (Read-Intensive) on Friday afternoon.

The fundamental problem of traditional database management is cognitive latency: between the degradation event (bloat, an execution plan change, a subtle lock) and human corrective action, there is a time interval where money is lost (MTTR). Reaction-based management – waiting for the “CPU > 90%” alert – is obsolete.

This article is a technical deep dive into PostgreSQL performance. We will address memory management, concurrency via MVCC, index engineering, and query parameterization. And, crucially, we will demonstrate how Artificial Intelligence (AI) and platforms like dbsnOOp are transforming optimization from an unsustainable manual task into an autonomous and predictive engineering discipline.

1. Memory Architecture and Caching (Shared Buffers vs. OS Page Cache)

A common case in Postgres servers: you have 128GB of RAM, but tools like htop show little free memory and a lot of “cache/buffer.” While performance is acceptable, the fear of an Out-Of-Memory (OOM) Killer is constant. This scenario is generally not a problem, but a sign that PostgreSQL and Linux are working in partnership.

Unlike other DBMSs that try to manage memory in a monolithic and exclusive way, PostgreSQL adopts a Double Cache architecture. Understanding this dynamic is the first step to effective tuning.

shared_buffers and Double Cache

shared_buffers is the RAM area reserved by PostgreSQL to store data pages (8KB blocks) for reading and writing. No data manipulation occurs outside this area. If you want to perform an UPDATE, the page must be here.

If you come from Oracle or SQL Server, you are likely used to configuring this parameter to 70-80% of RAM. However, this is a critical mistake in PostgreSQL.

PostgreSQL relies heavily on the OS Page Cache (the Linux file system cache). If Postgres requests a page that is not in shared_buffers, Linux checks its own cache. If it is there, delivery is made via memory (fast). If you allocate 80% of RAM to shared_buffers, very little is left for Linux. This causes the Double Buffering phenomenon: the same data page resides duplicated in shared_buffers and in the little that remains of the Page Cache, while other hot pages are evicted to disk, generating unnecessary physical I/O.

A Proper Configuration:

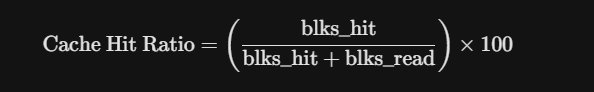

The starting recommendation is 25% of total RAM for shared_buffers. However, validation must be done via Cache Hit Ratio metrics.

-- Advanced Query for Cache Efficiency Diagnosis

WITH cache_metrics AS (

SELECT

sum(blks_hit) AS hits,

sum(blks_read) AS disk_reads,

sum(blks_hit + blks_read) AS total_requests

FROM pg_stat_database

WHERE datname = current_database()

)

SELECT

hits,

disk_reads,

round((hits::numeric / total_requests) * 100, 4) AS cache_hit_ratio_percent

FROM cache_metrics;

A healthy system should maintain this value above 99%. If it is lower, and your disk I/O is high, it is time to consider increasing shared_buffers or scaling the infrastructure.

The Golden Rule (and its exceptions):

For dedicated servers, start with 25% of total RAM for shared_buffers. It should rarely exceed 40% or 16GB-32GB in older versions, although in purely analytical read workloads (OLAP) that fit entirely in RAM, larger values may be justified.

OS Page Cache

The Linux operating system aggressively uses all unallocated RAM to cache file system files. Since PostgreSQL reads and writes to files, it benefits enormously from this. If a page is not in shared_buffers, PostgreSQL requests it from the OS. If the OS already has it in the Page Cache, delivery is made via memory (fast), avoiding physical disk I/O (slow).

work_mem

While shared_buffers is global, work_mem is allocated per operation within a session. It is used for sorts (ORDER BY), DISTINCT, and joins (Hash Joins, Merge Joins). If your application opens 500 connections and executes complex queries, and your work_mem is 100MB, you can theoretically demand:

500 × 100MB = 50GB of RAM

potential consumption = max_connections x work_mem

If the server has 32GB, the Linux OOM Killer will terminate the PostgreSQL process to save the kernel. Total collapse.

Conversely, a very low work_mem forces PostgreSQL to use temporary files on disk to sort data (Disk Merge Sort), which is significantly slower than QuickSort in memory.

Solution via dbsnOOp:

Adjusting work_mem globally is imprecise. dbsnOOp’s AI analyzes temporary file usage (temp_bytes in pg_stat_statements) and recommends dynamic adjustments, or even session-level changes for specific users, balancing OOM risk and performance.

Measuring Efficiency

It is fundamental to measure efficiency in PostgreSQL. The query below serves to calculate the Cache Hit Ratio. If the value is less than 99%, your shared_buffers might be undersized for the current load:

SELECT

'shared_buffers_hit_rate' AS metric,

(sum(blks_hit) * 100.0) / sum(blks_hit + blks_read) AS hit_rate_percentage

FROM pg_stat_database

WHERE datname = current_database();

Modern Tuning with ALTER SYSTEM

Forget manual editing of the configuration file subject to syntax errors. Use the SQL command to persist changes in postgresql.auto.conf.

-- Set shared_buffers (Requires restart)

ALTER SYSTEM SET shared_buffers = '16GB';

-- Set work_mem (Requires only reload)

-- WARNING: work_mem is per operation/node.

-- 100 connections x 64MB = 6.4GB of potential RAM just for sorting.

ALTER SYSTEM SET work_mem = '64MB';

-- Applies changes that do not require restart

SELECT pg_reload_conf();

2. Advanced Index Engineering

In a postgres-based infrastructure, hardly any operation will offer an ROI as large as a CREATE INDEX. A slow query taking minutes can start running in milliseconds. However, indexes have trade-offs.

The Fundamental Trade-off:

- Read (SELECT): Drastically accelerated (Logarithmic vs. Linear).

- Write (INSERT/UPDATE): Penalized. Each index is a redundant table that needs to be updated atomically with every write. A table with 10 indexes requires 11 physical writes for each INSERT.

Column Order (Cardinality)

In compound indexes (multicolumn), order matters. The column with the highest cardinality (largest number of unique values) and that is used in equality filters should come first.

- Scenario: Table issues with project_id (10,000 distinct) and status (3 distinct: ‘open’, ‘closed’, ‘wip’).

- Query: WHERE project_id = 42 AND status = ‘open’

- Wrong: INDEX(status, project_id) -> The database filters ‘open’ (millions of rows) and then searches for the ID.

- Correct: INDEX(project_id, status) -> The database goes straight to project 42 (few rows) and filters the status.

Error: Ignoring Advanced Index Types

B-Tree is the standard, but PostgreSQL shines in its extensibility.

- GIN (Generalized Inverted Index): Mandatory for JSONB, Arrays, and Full-Text Search. A B-Tree cannot efficiently index internal keys of a JSON.

- GiST (Generalized Search Tree): Essential for Geospatial data (PostGIS) and data types that overlap.

- BRIN (Block Range Index): For huge tables (Time-Series) physically ordered (e.g., by date). A tiny index that points to page blocks, saving gigabytes of RAM.

Maintenance: Bloat

PostgreSQL uses MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control) to ensure isolation and consistency. When you perform an UPDATE, Postgres does not overwrite the old data. It marks the old row (tuple) as “dead” (dead tuple) and inserts a new version of the row.

The Bloat Problem

These dead tuples occupy space, whether physical or logical in the OS. If not removed, the table “bloats,” and a Full Table Scan on a bloated table needs to read gigabytes of “garbage” to find live data, which destroys I/O performance and cache effectiveness.

The process responsible for cleaning is Autovacuum. In default settings, it is often too conservative for high-traffic databases and quickly hits the cleanup limit, leaving behind many dead tuples that exceed its capacity.

Transaction ID Wraparound

PostgreSQL uses 32-bit transaction identifiers (XID). If the database processes 4 billion transactions without a successful VACUUM to “freeze” old data, the counter wraps around. To avoid data corruption, PostgreSQL stops accepting writes. The database enters read-only mode until a manual VACUUM (which can take days) is completed.

Advanced Query for Bloat Estimation:

This query is essential for DBAs to identify tables needing a VACUUM FULL or pg_repack.

SELECT

current_database(), schemaname, tablename,

ROUND((CASE WHEN otta=0 THEN 0.0 ELSE sml.relpages::FLOAT/otta END)::NUMERIC,1) AS tbloat,

CASE WHEN relpages > otta THEN (relpages-otta)*8/1024 ELSE 0 END AS wasted_mb

FROM (

SELECT

schemaname, tablename, cc.reltuples, cc.relpages, bs,

CEIL((cc.reltuples*tupsize)/bs) AS otta

FROM (

SELECT

ma.schemaname, ma.tablename,

(SELECT substring(ma.attname FROM 1 FOR 60) FROM pg_attribute pa WHERE pa.attrelid = ma.attrelid AND pa.attnum > 0 AND NOT pa.attisdropped LIMIT 1) AS any_attname,

(SELECT avg(pg_column_size(ma.tablename::regclass)) FROM pg_class) as tupsize

FROM pg_tables ma

) AS tbl

INNER JOIN pg_class cc ON cc.relname = tbl.tablename

INNER JOIN (SELECT current_setting('block_size')::NUMERIC AS bs, 23 AS hdr, 4 AS ma) AS constants ON 1=1

) AS sml

ORDER BY wasted_mb DESC LIMIT 10;

Caution: This query estimates bloat statistically. For lock-free cleaning, consider tools like pg_repack.

Automation with dbsnOOp:

dbsnOOp’s AI analyzes the actual Workload. It identifies indexes that are never used (idx_scan = 0) but consume space and write I/O, suggesting their removal. Simultaneously, it detects frequent Sequential Scan patterns and generates the exact DDL command to create the ideal “Missing Index,” including the creation of partial or covering indexes.

[Deep dive into bloat maintenance in this complete guide focused on PostgreSQL]

3. Query Performance and Parameterization

At the heart of ERP and Retail systems, performance is dictated by the interaction between the Application and the Query Planner.

Hard Parse vs. Soft Parse Cost

When PostgreSQL receives a SQL query, it needs to:

- Parse: Check syntax.

- Analyze: Check if tables/columns exist.

- Rewrite: Apply rules/views.

- Plan: Estimate costs and choose the best path (Index Scan vs Seq Scan, Nested Loop vs Hash Join).

- Execute: Run the query.

Step 4 (Plan) demands much of your computational capacity.

Literals Error (Retail Case Study)

Imagine an e-commerce sending queries like this:

SELECT * FROM pedidos WHERE cliente_id = 105;

SELECT * FROM pedidos WHERE cliente_id = 902;

For PostgreSQL, these are different queries. It replans everything each time. This causes:

- CPU Burn: The server spends more time planning than executing.

- Plan Cache Pollution: The plan cache fills with non-reusable garbage.

- Suboptimal Plans: The planner may choose a bad plan based on statistics of a specific ID that does not apply to others.

Diagnosis with pg_stat_statements

This extension is mandatory: it normalizes queries (replaces values with $1), allowing you to see which query patterns consume the most resources.

-- Identify the most costly queries in aggregate

SELECT query, calls, total_exec_time, mean_exec_time, rows

FROM pg_stat_statements

ORDER BY total_exec_time DESC

LIMIT 5;

If you see the same query structure repeated with different literals and unstable plans, you have a parameterization problem. The solution is to refactor the application to use Prepared Statements.

4. The Limits of Manual Management

Adjusting shared_buffers, creating correct GIN indexes, monitoring Bloat, and fixing query parameterization for a single instance might be feasible, but doing this for dozens of microservices, 24/7 while the dev team releases new features weekly, can be humanly impossible.

Traditional monitoring (Zabbix, Datadog, CloudWatch) is reactive. It shows “CPU at 90%,” but doesn’t say why: was it an aggressive autovacuum? A non-parameterized query? A bloated index? Your team still needs to waste time and engage your experts in an investigation – troubleshooting.

This is where database engineering evolves into Predictive Observability with dbsnOOp.

The Autonomous DBA for PostgreSQL

dbsnOOp goes far beyond a graphing and monitoring tool: it is an intelligence platform that automates a DBA’s expertise.

Unified View

dbsnOOp centralizes the view of your monitored instances. The tool uses Machine Learning algorithms to create dynamic baselines and learns that it is normal for CPU to rise at 02:00 (backup), but if it rises at 10:00, it is an anomaly requiring an alert, even if it doesn’t reach the critical threshold.

Predictive Analysis and RCA (Root Cause Analysis)

Instead of a vague alert, dbsnOOp correlates events.

- Problem: High latency in Sales API.

- AI Diagnosis: “Latency increased due to Lock Waits on table inventory. The root cause is transaction PID 12345 (user job_stock) holding a RowExclusiveLock for 45 seconds.”

- Suggested Solution: SELECT pg_terminate_backend(12345); and recommendation to review the Job’s query.

Query Performance

The platform understands the context of engine metadata and translates this into deep analysis, allowing professionals of different levels to make quick decisions without relying on complex system commands.

Text-to-SQL

Allows writing queries in natural language which are converted into a query executed on the system of your choice, whether PostgreSQL or not. The result arrives in the form of a table within the platform itself. Thus, access to data from diverse technologies is not limited only to specialists.

Automated Index Management

dbsnOOp analyzes the actual (not theoretical) usage of indexes.

- Dead Weight Removal: Identifies indexes that receive many writes (high cost) but are never read (idx_scan = 0), suggesting their safe removal.

- Creation Suggestion: Detects recurrent slow queries and generates the exact DDL command (CREATE INDEX…), considering cardinality and data type (JSONB, Text, etc.).

Let AI Manage Complexity

The era of manual and static PostgreSQL configuration is over: trying to manually balance the complex matrix of memory, concurrency, and I/O parameters is inefficient and risky.

Adopting a platform like dbsnOOp transforms your operation. You stop wasting energy fighting fires and trying to guess configurations and start acting as a data architect, making decisions based on predictive and precise diagnostics.

- Reduce MTTR from hours to minutes.

- Optimize Cloud Costs by eliminating resources wasted by bad queries.

- Ensure Stability before the client notices slowness.

Don’t rely just on luck or obsolete golden rules. Schedule a meeting with our experts or watch a demonstration of dbsnOOp in practice and see how Artificial Intelligence can unlock your PostgreSQL’s true performance.

Schedule a demo here.

Learn more about dbsnOOp!

Learn about database monitoring with advanced tools here.

Visit our YouTube channel to learn about the platform and watch tutorials.

Recommended Reading

- Why Is My Cloud Database So Expensive? A practical analysis of the main factors inflating your AWS RDS, Azure SQL, and Google Cloud SQL bills, connecting costs directly to unoptimized workloads, over-provisioning, and a lack of visibility into actual consumption.

- Locks, Contention, and Performance: A Technical Study on Critical Database Recovery: This article offers a technical deep dive into one of data engineering’s most complex problems. It details how lock contention can paralyze a system and how a precise analysis of the lock tree is crucial for recovering databases in critical situations.

- Indexes: The Definitive Guide to Avoiding Mistakes: A practical and fundamental guide on the highest-impact optimization in a database. The text covers the most common mistakes in index creation, such as over-indexing and wrong column order, which can degrade both read and write performance.